By Rachael Graf, Community Engagement Coordinator

Whether you’re huddled around a campfire or snuggled under blankets in your living room, fall is the perfect time to tell stories of intrigue. Our Outer Banks national parks have all played vital roles in both American and world history, and each park has its own unsolved mystery.

Cape Hatteras National Seashore: The Wreck of the Mysterious “Ghost Ship”

The Carroll A. Deering was built in 1919 in Bath, Maine and wrecked on January 31, 1921. Photo Credit: National Park Service, The Mariner’s Museum.

Cape Hatteras National Seashore, which encompasses Bodie Island, Hatteras Island and Ocracoke Island, has its fair share of ghost stories, several of which are associated with the Outer Banks’ notorious distinction as “The Graveyard of the Atlantic.” While many of these ghost stories are not rooted in fact, at least one of them is: The “Ghost Ship” of the Outer Banks.

On Jan. 31, 1921, the five-masted schooner Carroll A. Deering was sailing from Virginia to the Caribbean when it ran aground on Diamond Shoals. The 1,879-ton ship was beaten by the wind and waves — a total loss. Conditions were so bad that a wrecker and a lifesaving crew couldn’t reach the ship for four days.

When rescuers led by Capt. James Carlson were finally able to board the Carroll A. Deering on the morning of Feb. 4, 1921, they found it abandoned. Everything of importance was missing, yet a table was set as if the ship’s crew was preparing to eat. According to one source, the only living being that greeted the rescuers was a six-toed cat that had somehow survived the wreck.

Dumbfounded, Capt. Carlson and his men returned to shore. So strange and disturbing was the shipwreck that an agent from the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) made a trip to the Outer Banks in July 1921 to investigate. While the FBI subsequently pursued leads and theories such as pirates, gangsters and general mutiny, the mystery was never solved.

To this day, the fate of the Carroll A. Deering crew remains unknown.

Wright Brothers National Memorial: How did “Kill Devil Hills” get its name?

Big Kill Devil Hill when the Wright Brothers arrived in the Outer Banks (1901). Photo Credit: National Park Service.

No one seems to know exactly how the town of Kill Devil Hills earned its unique name, but theories abound.

It is known that American Indians, seafarers and settlers all called the area home for centuries, but the name “Killdevil Hills” didn’t appear on maps until 1808. The “Kill Devil Hills Lifesaving Station” was established seven decades later, in 1878.

Some say Kill Devil Hills earned its name from the rum that washed ashore from shipwrecks along the Outer Banks – some said it was strong enough or in such great quantity it could “kill the devil.”

William Byrd II used similar language in his journal (1728) in which he detailed the work of exploring and defining the boundary line between Virginia and North Carolina: “Most of the Rum they get in this Country comes from New England, and is so bad and unwholesome, that it is not improperly call’d ‘Kill-Devil.’”

Another explanation for the town’s name comes from the population of Killdeer birds, a type of plover, that live in the Outer Banks. According to the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Killdeer are the largest member of the plover family and are about the size of a robin. They enjoy wide open spaces and emit a “kill-deer” sound, which is how they earned their name. It is possible that “Killdeer Hills” was once a name for the sand dunes we’re familiar with today.

What does all of this have to do with the Wright brothers, you may wonder?

A lot!

When Orville and Wilbur Wright came to the Outer Banks in the early 1900s to test their various airplane prototypes, they spent a significant amount of time on a group of sand dunes that were referred to as “the Kill Devil Hills.”

At the time, the sand dunes were huge. “Big Kill Devil Hill” — where the monument to the ingenious brothers stands today — was 100 feet tall and “West Hill” was 60 feet tall. Over the years, Orville and Wilbur would walk up and down “the Kill Devil Hills” thousands of times before their first successful heavier-than-air, controlled, powered flight on Dec. 17, 1903.

It could be said that the Wright brothers officially put Kill Devil Hills on the map: 50 years after the first flight, Kill Devil Hills officially adopted its nickname and became the town it is today.

Fort Raleigh National Historic Site: The Curious Case of the Disappearing Englishmen

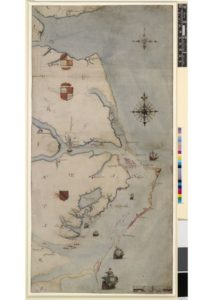

John White’s watercolor map of the east coast. Photo Credit: National Park Service.

Fort Raleigh National Historic Site has always been shrouded in mystery, as Roanoke Island was the last known site of the 1587 English colonial experiment that vanished by 1590. Numerous unsubstantiated legends and lore surround the “Lost Colony,” as it later became known. No one can say definitively what happened to the colonists, but there are other mysterious disappearances recorded prior to 1590.

In March 1584, Sir Walter Raleigh obtained a patent to send out expeditions to claim land in the “New World.” In April 1584, Philip Amadas and Arthur Barlowe, two English explorers, made contact with the Carolina Algonquian who lived on the Outer Banks and brought Manteo, a Croatoan member of the Carolina Algonquian, and Wanchese, a Roanoac member of the Carolina Algonquian, back to England with them.

Nine months later, on Jan. 6, 1585, Queen Elizabeth I knighted Raleigh, naming him governor of the newfound Outer Banks territory (Raleigh called it “Virginia”; he would never actually travel to see the land). In April of that same year, Sir Richard Grenville and Ralph Lane returned to the Outer Banks with Manteo and Wanchese — bringing at least 100 Englishmen with them. Grenville left the men under Lane’s supervision and departed.

In June 1586, Sir Francis Drake, a nefarious character famous for circumnavigating the globe, arrived on Roanoke Island. He found Lane, the leader of the colony, and the colonists in dire straits — Lane had attacked the Roanoac members of the Carolina Algonquian and killed Chief Wingina, and he and his men suffered for it. After a violent storm, Lane and many of the colonists decided to return to England with Drake. Some, however, were abandoned.

The journal from one of Drake’s ships states:

“Those gentlemen and others, as soon as they saw us, thinking we had been a new supply came from the shore and tarried certain days, and afterwards we brought thence all those men with us, except 3 who had gone further into the country and the wind grew so that we could not stay for them.”

Two weeks later, Grenville arrived at Roanoke Island with the supply fleet. He did not find the three missing men and discovered the place was deserted. He then left 15 more soldiers to hold the fort, promising to return the next year. That was the last time a European would see any of those 15 men alive.

When the English colonists arrived at Roanoke Island in 1587, they learned from the Croatoan tribe that the 15 men had been attacked: two had been killed and 13 had escaped, never to be seen again.