This month, we join with the National Park Service in celebrating and honoring Black History Month by sharing stories about African American history in the Outer Banks and in our Outer Banks national parks. Note: This post was originally published in February 2020.

Paul Laurence Dunbar, far left back and Orville Wright, center back. Photo: National Park Service.

In 1890 at a small rural high school in Dayton, Ohio, an unlikely friendship was struck up between Paul Laurence Dunbar, an aspiring poet, and Orville Wright, an aspiring inventor/aviator.

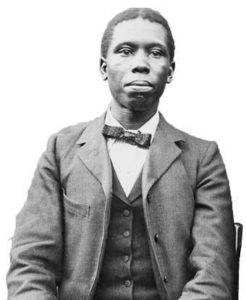

Dunbar was born in Dayton, Ohio, on June 27, 1872. He was the only African American student in his class at Ohio Central High School. As he had a gift for the written word, he was the editor of the school’s newspaper and also participated in the literary and debate societies.

In those early years, Paul and Orville often used their talents to help each other with class assignments – Paul having a talent for writing and Orville making easy work of math and science.

Orville was entrepreneurial from a young age – he started a newspaper of his own, West Side News in April of 1890, and soon made his elder brother, Wilbur, editor. Dunbar desired to pursue a career in journalism and also created his own newspaper for distribution in Dayton’s African American community, the Dayton Tattler, which Orville printed in December of 1890.

Paul Laurence Dunbar. Photo: National Park Service.

While the Wright brothers would not become well known until 1903, Dunbar gained notoriety a few years after graduating from high school in 1891. Unfortunately, Dunbar’s dream of being a journalist did not materialize right away, as he did not have the funds to further his education, and he was barred from the majority of jobs in the area because he was African American.

According to a biography on Dunbar’s life published by Wright State University, Dunbar worked as an elevator operator while continuing to write poetry.

In 1892, one of Dunbar’s former teachers invited him to speak at the Western Association of Writers convention in Dayton. Dunbar’s experiences during and after the convention led him to self-publish his first book of poems, Oak and Ivy, in 1893: “He sold the book for $1 to people riding in his elevator, eventually recovering his initial $125 investment.”

Dunbar’s work quickly became popular, earning him the acclaim of many, including that of Frederick Douglass. As Dunbar’s work became more widely known, he traveled around the United States and England giving readings.

A gifted and ingenious young man who never gave up, Dunbar launched a literary career that shaped both history and American literature. As the National Park Service notes, Dunbar was “…an American poet and author who was best known in his lifetime for his dialect work and his use of metaphor and rhetoric, often in a conversational style. …He produced twelve books of poetry, four novels, four books of short stories, and wrote the lyrics to many popular songs. Dunbar became the first African American to support himself financially through his writing.”

Sadly, Dunbar passed away at the age of 33 at his mother’s home in Dayton on February 9, 1906, following a battle with tuberculosis.

The National Park Service recognizes Dunbar as “..an experimenter, and innovator who tried to express his feelings and vision in the many forms that literature offers. He has been called the ‘poet laureate of his people,’ yet he has become a voice for all people. Through all of his writing runs the desire to explain the ambitions, hopes, and dreams of African Americans. He strived to show to the world the reality of blacks as caring, thoughtful, creative individuals, as people, not stereotypes. He was an African American struggling with the racism and oppression of his time, and yet he is a spokesperson for all who have dreams unfulfilled.”

In Dunbar’s own words: “I did once want to be a lawyer, but that ambition has long since died out before the all-absorbing desire to be a worthy singer of the songs of God and nature. To be able

to interpret my own people through song and story, and to prove to the many that

after all we are more human than African.”

To learn more about Paul Laurence Dunbar and his legacy, you can visit the Flight Room at Wright Brothers National Memorial or visit his home, which is now a part of Dayton Aviation Heritage National Historic Park. Click here to read a selection of Dunbar’s poems.